Court Lodge

At an Annual Parish Meeting, Alma Saker gave a talk on her experiences at Court Lodge and the Fairbridge Society.

On Wednesday 3 March this year I was listening to Radio Kent and Andy Garland the presenter was asking about John Howard Mitchell House. As it happened I knew quite a lot about this house. It had been bought by a wealthy benefactor for the Fairbridge Society in memory of her son. We knew it and still know it as Court Lodge, the house next to the Church.

This is really about the lost children of the Empire – children who had emigrated through the auspices of various societies to Farm schools in Canada, Africa and Australia. A lot of these children, obviously now adults have come forward to tell their stories of slave labour, of lies and of ill treatment.

Kingsley Fairbridge the founder was born in 1885. In 1909 at the age of 24 he had an idea – a vision – to people the British colonies with children who stood a poor chance in the prevailing conditions in England and so help them – the children and the Empire. Such was his faith that he persuaded 50 fellow undergraduates of the need for this idea, so much so that they formed a committee of The Futherance of Child Emigration to the Colonies. Kingsley Fairbridge was instructed to carry this idea forward, to collect money , to find a way. His fellow undergraduates each promised 5 shillings old money = £12 plus!

In less than three years he and his new wife founded the first farm school in Western Australia at Pinjarra, a small village about 55 miles from Perth. His aims for underprivileged children were:

1. that children of all denominations were received into the society and the Society would provide for each one in the faith to which he/she belonged.

2. the happiness and wellbeing of the children were the first considerations of Fairbridge

3. Each child was given the opportunity of being trained for any occupation for which he or she was best fitted

4. There was a system of after- care which provided fro the well-being of all until the age of 21 and after that if required.

In fact, ninety –eight per cent of those sent to the Commonwealth made good. This report was written in 1951.

I joined Fairbridge during the summer of 1951 as assistant to the Matron, Mrs Reeves. Court Lodge was, and still is I am sure, a beautiful house. We worked hard to make it into a comfortable home – if a little stark. We made up beds – and I don’t just mean making them up with clean linen – I mean starting from scratch – they had been delivered in flat back form and we actually made the beds.

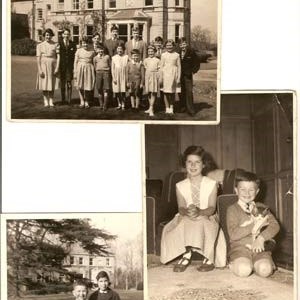

By late Summer of 1951 we were ready to receive the first party of children. They came in 1s and 2s and in one case a little family group of 3 children. By the middle of October we had 20 children plus 3 adults, who were, in fact, Australian, and were going to escort the children to Australia. Here, at John Howard Mitchell House (as Court Lodge was then called) the prime object of the reception centre was to let the children get to know each other, to learn to live together and to adapt to their surroundings. Most of them having come from life in a crowded town they had no idea what life in the country was like so Knockholt gave them an inkling of the countryside.

In the very early stages of the children arriving, Mrs Reeves and I did all the chores, but, thankfully she was soon able to employ a lady to cook and another to clean. We were also fortunate that some kind person donated an automatic washing machine – a Bendix no less! Of course there were some children who were homesick and needed extra TLC but my instructions were to mother them not smother them. Matron also made a couple of rooms available to parents who wished to visit their children before they sailed to Australia. Fairbridge children were NEVER told that they were orphans or unwanted as some authorities and societies had done.

That first party of children was given a Royal send off. The Duke and Duchess of Gloucester came on the 5 th November 1951 to officially open Court Lodge as John Howard Mitchell House and to talk to the children and have tea with them. A few days later the children sailed from Tilbury to Australia to embark on a totally new way of life.

An Account by One of the Fairbridge Children

Knockholt to Australia

It was 1953 when my mother fled from my violent father and later divorced. I was 4 and a half years old, my brother Paul was just a baby.

We moved to London from the West Country and lived with my Gran in a one bedroom flat for a short time before being evicted. From London we went to Margate in Kent and after living in Church halls for a while were offered a home and Mum a full time clerical position with the Council.

The following 5 years weren't easy but we coped. My Granny became my Mum while Mum worked endlessly as the provider for our little family.

September 1958 – The moment never escapes me the day Paul and I had walked home from school for our usual cooked lunch.

Without lunch, without our usual fuss and cuddles Granny stood quietly at the top of the stairs and calmly instructed us to return to school.

She looked down and simply said ‘Good-bye'. Unbeknown to us she died an hour later.

With no-one to take care of us while Mum worked, life for my brother, Paul and I took a dramatic turn the day a strange man collected us from our home in Birchington, Kent and drove us to Knockholt.

Vivid memories recall my 6 yr old brother crying and vomiting on the long and pained journey. As a 10 year old, I knew only to comfort him and reassure him we would see our mummy soon.

I remember John Howard Mitchell House for its Grandness, its opulence, the many chimneys and large windows and the magnificently manicured gardens.

We were the only children on arrival and caregivers spoilt us with attention and kindness.

I recall a large map of Australia on a lined oak panelled wall in the playroom. We ate fine food off fine china, slept on clean quality linen and staff pandered to our every need.

Paul and I settled into the little Primary School opposite and as spring approached we were unaware that the odd trip to London to buy clothes and visits from doctors and officials was in preparation for our journey to Australia.

As weeks passed other children arrived, a total of 13, Paul being the youngest, 2 of us were 10, the rest aged from 12 to 15yrs. All but one was to be sent to another land.

Mum stood with an official and showed Paul and I where Australia was on the map. Paul flatly refused to go anywhere and just wanted to go home. It was not a good time.

April 1959 –

A mixture of feelings was felt over the following 6 weeks as we cruised our way to an unknown land. Naivety and the novelty of new surroundings disguised uncertainty and we were among children we knew although the older kids were left pretty much to themselves. The younger ones were cared for by two young ladies, one a nurse, the other a teacher returning to Australia.

Paul shared the girls' cabin and suffered terribly from home-sickness. I would read a bed-time story each night. We wrote in our diary daily – an amusing read these days.

Calls into various Ports were a life-time experience and memorable.

June 1959 –

Our arrival to Sydney Australia was also very memorable and although a trip to the zoo and lots of ice-cream would soften the blow initially, the 300 km odd extremely cold night on the train into Australia’s barren outback and early morning arrival to Molong and onto Fairbridge would be a harsh reality.

After a long wait in the freezing cold we were greeted and crammed in along with luggage into a small truck, its canvas roof providing little shelter.

I won't go into Fairbridge's history as this is well documented but the early dark hours of that morning can never be forgotten.

After a warm drink we stood quietly and waited as each child was escorted away and taken to their designated cottage.

Horror struck, as one by one we were parted and apart from one I never saw my friends again. I was lucky Beryl my little 10 yr old playmate would live in the same cottage but Paul went on his own. That destroyed me and Paul cried uncontrollably.

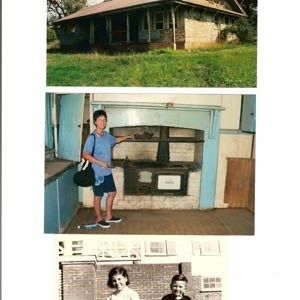

I lived in Molong cottage, one of three girls' cottages and one of the first built in 1938.

They were all similar in design from what I gather. Small kitchen with an old wood-fuelled stove, a large open plan lounge/dining room, a locker room for clothes and to get dressed in, a large dormitory with 16 kapok plastic-covered mattresses on wired camp-type beds and a large bathroom that consisted of 2 showers and 2 toilets.

An untrained cottage-mother looked after the children in the 15 odd cottages, some were okay, and others weren't. Children's experiences seem to vary considerably over the years and from cottage to cottage.

My cottage-mother was strict – very strict. There was a lot of cleaning in our cottage, we were forever washing the timber floors, waxing and then polishing them madly.

The girls were jealous because I had a parent and at times they bullied Beryl and I.

Of course I look back now and realise the poor girls didn't know their parents, even if they had any parents or siblings.

We were unloved and no caring or emotion was ever expressed. This was heartfelt sadness among most who stayed there it seems.

It's institutional living as I see it. – It's cold, calculated and unforgiving. Abuse happened and there was no-one to turn too.

There was no communication with the outside world, no communication with family in England, and that's if you knew you had any.

Discipline was discipline in the harsh sense and that of the day. Caning happened; my brother was caned regularly for wetting his bed, and in the early days for coming to see me.

Paul was banned from seeing me and that would be my pet hate for ever more.

Fairbridge ran self-sufficiently and under supervision the boys and girls from the age of 12 yrs were rostered to work on the farm. They milked the cows twice a day, attended to the vegetable gardens, the pigs, the sheep, made the stodgy bread, the horrible porridge and cooked the meals for the main Dining Room.

Paul and I attended a two class roomed school at Fairbridge, sadly I saw little of Paul and he had already become a sad little boy and a loner.

After 2 years Mum who had come to Australia won her battle to have us home but after 6 months and three different flats all of which unsuitable for children, we were sent back to Fairbridge. Second time round I have no recall of Fairbridge until the day (18 months later) we were told we were being sent to Melbourne where Mum now lived. It was goodbye Fairbridge and hi to the tough world outside.